Initial Analysis of College Scorecard Earnings and Repayment Data

By Ben Miller and Antoinette Flores

This first appeared on americanprogress.org

The Obama administration unleashed a massive deluge of data on the higher education community this month. This set of figures, dubbed the College Scorecard, represents a detailed and unprecedented look into the earnings and loan repayment rates of undergraduate federal student aid recipients going as far back as the late 1990s. These data make it possible to see for the first time how undergraduate students receiving aid at thousands of colleges across the country are faring in the workplace and their status on repaying student loans, among many other indicators. For colleges that do a good job, the data are a chance to bring recognition not normally bestowed by publications such as U.S. News & World Report, which is known for producing an annual ranking of the “best” colleges. But for institutions that do not serve students well, hiding in the shadows of misinformation just got a lot harder.

The full extent of the information released will take months to process. But an initial analysis by the Center for American Progress shows a federal student aid system for which the results are positive but headed in the wrong direction, especially in the for-profit college sector. Overall, nearly two-thirds of undergraduate college students who received financial aid and entered repayment in 2010 and 2011 are repaying their loans, and 10 years after entering college, two-thirds are earning more than what a high school graduate is expected to make. But the data show that results have been declining over time, with more students failing to repay their loans and more students’ earnings falling below $25,000 a decade after entering college.

Federal student aid is a powerful tool that provides opportunity and access to millions of undergraduate students each year. But it is also not without risk. Growing college prices, stagnant family incomes, and declining state support for higher education mean that the most vulnerable students must increasingly use student loan debt to finance their educations. Absent more work being done to address college affordability and to root out the bad actors, these trends are only likely to get worse.

This data release is the culmination of a process that started more than two years ago when the Obama administration announced an ambitious plan to shake up higher education by rating colleges and universities. While the actual ratings never happened—they were dropped in June—a gigantic set of higher education data has been released in their place.

Earnings

The use of earnings as a measure of college quality is a contentious issue. While students clearly care about getting good jobs after college, many institutional leaders and others do not like the idea of boiling down education to simply economic outcomes. Earnings by college also present a methodological challenge because the type of program students choose is likely to have a large influence on what they ultimately make. After all, someone who receives a business degree is almost always going to earn more than someone who earns a teaching degree.

The College Scorecard presents a way to reach a compromise between the two arguments about earnings. It includes a variable that looks at the percentage of all students who received federal aid and are now earning more than $25,000—a figure that roughly approximates what a high school graduate makes. The nice thing about this variable is that it judges colleges less on what their students actually make and more on the college’s ability to provide a minimum amount of economic return.

Unfortunately, the data show that an increasing share of undergraduate students getting federal aid are failing to exceed this $25,000 earnings threshold, even 10 years after entering college. Of undergraduates who first entered college in 2001 or 2002 and received federal aid, nearly one-third made less than $25,000 10 years later. That is a slight increase from students who entered in 1997 and 1998, only 30 percent of whom had earnings below the threshold.

More distressing is the sheer number of for-profit colleges from which a majority of former students fail to earn at least $25,000. Of the more than 1,100 for-profit colleges and universities with available data for the 2001 and 2002 entering-college cohorts, 57 percent had fewer than half of their students earn at least $25,000. By contrast, just 8 percent of nonprofit and 13 percent of public colleges are in the same situation.

Repayment

The federal government’s current way of judging student loan performance by college is the cohort default rate. This measure looks at the percentage of students who default on their loans within three years of entering repayment. While looking at default rates seems like a good way to judge student loan performance, this measure is unfortunately vulnerable to manipulation, as colleges can place borrowers on loan deferments or forbearances that allow them to avoid making payments—and thus not default—even as the borrowers make no progress toward paying down their loans.

The College Scorecard addresses cohort default rate shortcomings by producing a new loan repayment rate. This measure looks at the percentage of all borrowers who did not default on their loans and also made enough payments to reduce the amount of money they owe by at least $1.

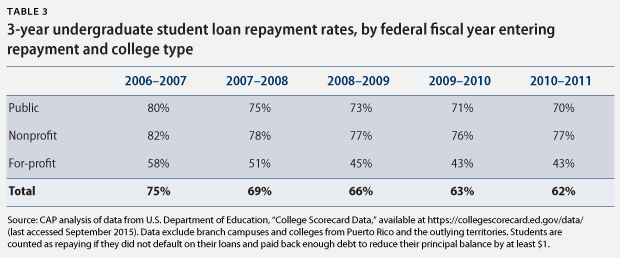

According to CAP analysis of College Scorecard data, the percentage of undergraduate borrowers who are successfully repaying their loans after three years has been steadily declining from those who entered repayment in 2006 and 2007 to those who entered in 2010 and 2011. This decline is particularly acute at private, for-profit colleges, where the three-year loan repayment rate fell from 58 percent in 2006–2007 to 43 percent in 2010–2011.

The drop in loan repayment rates is of particular concern because an analysis of repayment rates after one, three, and five years across different cohorts shows that they do not change much for a given set of borrowers. For example, in the 2006–2007 cohorts, 82 percent of borrowers from public colleges were repaying their loans after one year. After five years, that rate had only fallen slightly to 80 percent. This suggests that the more-recent cohorts that feature increasingly lower three-year repayment rates are unlikely to improve when five- or seven-year repayment data are available.

Conclusion

Although still just an initial cut of the data, this analysis of the College Scorecard shows that the overall results for college students are still positive—a majority of students are repaying their loans and most are earning more than $25,000. But the trend is headed in the wrong direction, particularly in the for-profit college sector. More must be done to ensure that current patterns do not persist.

Ben Miller is the Senior Director for Postsecondary Education at American Progress. Antoinette Flores is a Policy Analyst for Postsecondary Education at the Center.

Author Information

|

Center for American ProgressPosted on 25 September 2015 |

| The Center for American Progress is an independent nonpartisan policy institute that is dedicated to improving the lives of all Americans, through bold, progressive ideas, as well as strong leadership and concerted action. Our aim is not just to change the conversation, but to change the country. | |

| Visit Website | Follow @amprog |